I’ve been here four weeks now. It’s flown by and at times, has felt a bit overwhelming. But it’s already been one of the most stimulating, enriching experiences of my life. If my visa gets cancelled tomorrow and I’m deported as a dangerous leftist (it’s happened to others), I’ll always be grateful for my month in Newark.

The main reason for that is the brilliant scholars I’m having the privilege to work with. If they learn half as much from me as I’m learning from them, I’ll be happy.

With a class of up to 80, it’s quite hard to get beyond a sea of faces and the voices of the most extrovert. So I’ve set myself the task of meeting as many of the scholars as I can, informally, one-to-one. Already, they are giving me the kind of insights you can’t get from CNN.

So far, I’ve met a Chamorro mature student, who had to explain to me that this means her roots are in the US territory (i.e. colony), of Guam thousands of miles away in the Pacific. I’ve met another mature student who combines her study with a full-time job and has struggled to adjust to the US way of life since moving from Trinidad. She feels particularly self-conscious about her (lovely) accent. A third older scholar has been open about the fact that she has spent time in prison. I assumed that was years ago, but it transpires she wasn’t released until July. But most of the group are young, no older than 21. One was born in Israel and visits regularly, but is an astute critic of the Netanyahu regime, as worried about the future of his country of birth as his country of residence. Two of those I’ve met are here straight from high school, with roots in Guinea and Barbados and it’s hard not to feel very protective – and old. Another relative youngster, but mature beyond his years, with a troubled past and educated in the special needs system (for no reason that was apparent to me), used to work as flight cabin crew and asked for advice about his love life!

They are as different as any group of individuals, but with some things in common. All of them are stunningly good at expressing themselves and sharing their thoughts and feelings. They are politically engaged, but rarely with explicit party-political affiliations. That said, I doubt there is a single Trump supporter among them, although I’ve come to realise that his appeal, even in the liberal-leaning north-east, operates at layers I wasn’t aware of. A good friend told me on Sunday that she attended Trump’s rally in the South Bronx in May. She went, as a committed socialist, to try to judge the mood in a place where she has lived for many years and where it seemed Trump didn’t belong. Her experience confounded expectations. She reported one of the warmest, most friendly, communal atmospheres she remembers in her neighbourhood. It’s hard to imagine Trump, who thrives on division, being an agent of community cohesion, but this perhaps reflects the desperation of many Americans for a sense of solidarity, from almost any source.

I don’t think this assessment would be accepted by many of the students I’m working with. Given their backgrounds – almost all of them are young people of colour, many of them second generation immigrants – it’s no surprise that racism is high in their consciousness and Trump rightly seen as a key perpetrator of it. On Tuesday, we discussed the link between his use of racist slurs and tropes and the longer history of such bigotry in the US and beyond. I knew it could be a difficult session and it was. I’ll say more anon, but it was a fascinating insight into some of the murky waters of identity politics.

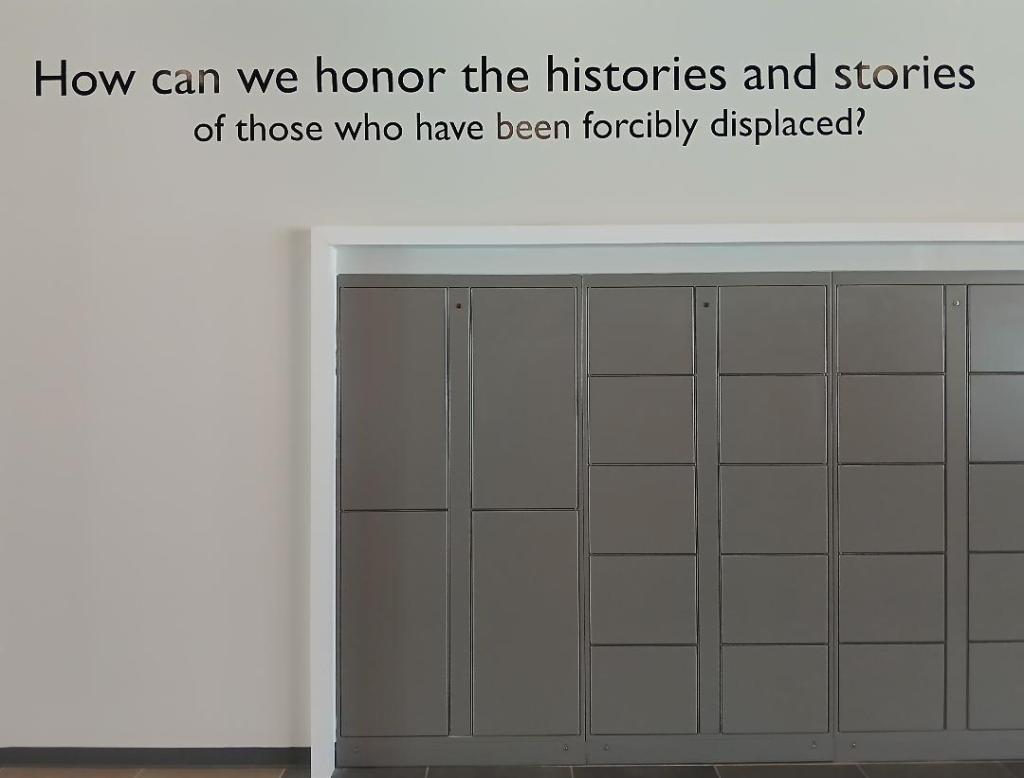

This is a tense time to be in the US and easy to be consumed with pessimism. But more than anything, what these young people give me is hope. At times, it’s almost impossible to believe they live in the same country as the reactionaries competing for political power. In large part, what we’re wresting with, here and beyond, is written on the walls of the building where we have our classes.

Leave a comment