The Chelsea neighbourhood captures the conflicting forces of New York City (NYC). It’s on the lower west side of Manhattan Island and used to be a working class community centred on the shipping industry and the piers along the Hudson River. It’s just south of Pennsylvania Station and Madison Square Garden, just north of Greenwich Village.

As in London, containerisation moved the loading and unloading of ships to another place (Newark and Elizabeth are NYC’s equivalents of Tilbury and Harwich). Like when the London docks closed, relocation generated a lot of unused land and buildings. In both cities, this precipitated a frenzy of speculative property development, much of it subsidised with public land and money.

The most grotesque manifestation of this in Chelsea is Hudson Yards. To some extent, if you’ve seen one outcrop of pretentious steel and glass phalli, you’ve seen the lot. Hudson Yards hasn’t brought the wholesale physical transformation that Canary Wharf has to the former dock area of the Isle of Dogs, partly because it has a lot of competition from other towers of mammon. But it still stands as a massive “fuck you” to the thousands of New Yorkers in desperate housing need. Last week, it was reported that 146,000 children in the city’s public schools were homeless during the past year, a 23% increase from the year before.

Since the 1930s, the most plentiful source of truly affordable rented homes in NYC has been public housing. It’s all over the city, including in some of its most affluent parts. I always enjoy strolling through Frederick Douglas Houses in the Upper West Side, two blocks from Central Park and thinking how infuriating it must be to the property pimps, like the President in waiting.

Public housing here, like council housing in London, is the best firewall against gentrification there is. I often walk around my home neighbourhood of Bethnal Green and think how different it would be, if it didn’t have lots of council housing that people have fought to keep.

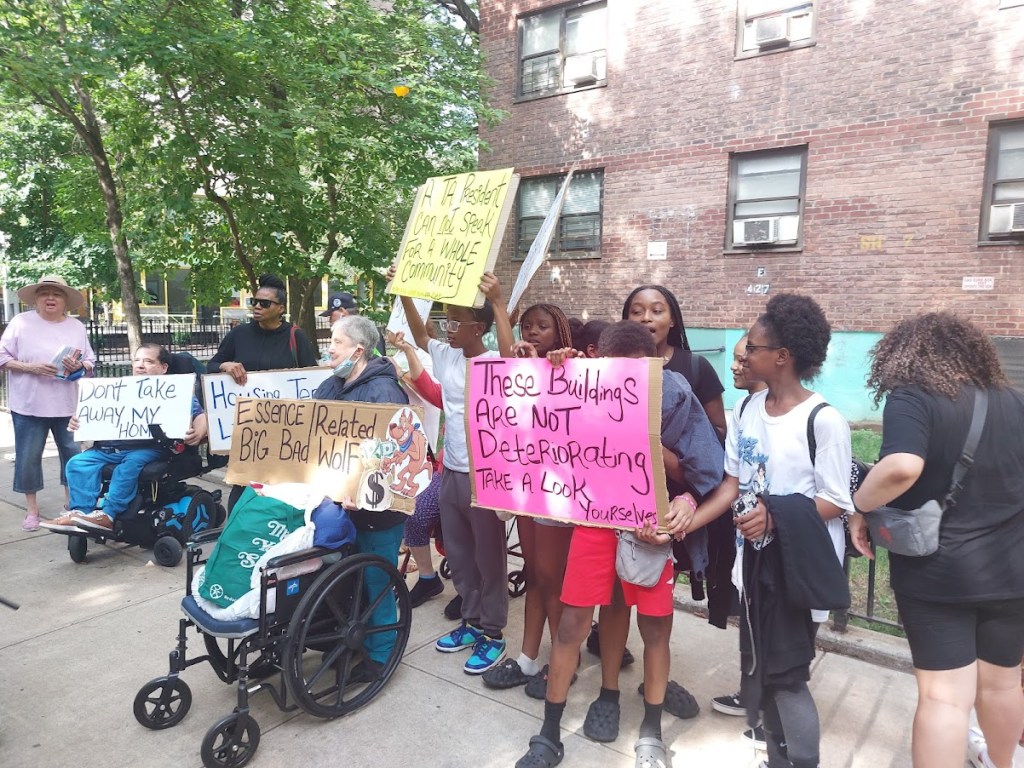

This dynamic is playing out in Chelsea. Close to Hudson Yards, but currently beyond the avaricious grasp of the property moguls, are two public housing developments, Elliot-Chelsea Homes, where at least 2,500 working class tenants live. Now, the New York City Public Housing Authority (NYCHA) is lining Elliot-Chelsea up for demolition and disposal. NYCHA’s deep-rooted problems are well documented. But as in the UK, the policy response of privatisation is a temporary fix that will lead to the permanent destruction of a working class community. It will mean less secure, non-market rented homes, when the city needs far more.

Just across 9th Avenue from Chelsea-Elliot is the Penn South housing cooperative. Completed in 1962 and inaugurated at a ceremony addressed by President Kennedy, this is one of the numerous NYC cooperatives sponsored by the city’s trade unions.

Penn South is home to about 5,000 people, living in 2,820 apartments in 15. 21-storey blocks. It has retained its “limited equity” cooperative status, meaning residents can’t sell their homes – which would easily fetch $1 million – on the open market. Like public housing, Penn South is an antidote to toxic property speculation.

I’ve had the pleasure of meeting several long-time Penn South residents during this trip. All of them say living there has enabled them to do things in their lives that wouldn’t have been possible otherwise. They include teachers, people who worked for non-profit social justice campaigns and artists. One of Penn South’s former residents was Bayard Rustin. He was living there when, among other things, he played a leading role in organising the 1963 March on Washington.

The people I’ve met at Penn South, like many others elsewhere, understand the true value of housing. For them, it’s something that helps you make a life, not make a lot of money. In the sardonic words of Ira Glasser, who has lived at Penn South since it opened, “it was so successful, they made sure it would never happen again”.

Actually, there were limited-equity housing co-ops built in NYC after Penn South, but the thrust of Ira’s comment is right. Any housing that isn’t primarily intended for profiteering, whether it’s public housing or mutual co-op, is anathema to Trump and his kind, especially if it’s in the type of area, like Chelsea, that they see as a gold mine. So, it’s excellent to learn that Penn South’s status as a non-profit co-op is protected until at least 2050, by when Trumpism and its ways might be a distant bad memory and more people will have the chance for full lives, instead of the shadow existence imposed by a housing system that knows the price of everything – and the value of nothing.

Leave a comment