A core element of the course I’ve been teaching at Rutgers is reparations. We’ve had guest speakers on the subject and students have been given information about how to join reparation campaigns. Racism, in its many guises, has been a constant theme in our classes and the legacy of slavery often comes up as its root cause.

Ever since I developed my fascination with the US, I’ve been convinced that, until or unless, the country fully comes to terms with this part of its history, it will remain fractured and discordant. At times, particularly during the height of Black Lives Matters, it has felt that a breakthrough might be getting closer. But the election of Trump has moved that further away. There are many unknowns about his return to power. But it is certain that he will not be leading a national period of reflection on 250 years of black enslavement.

I recently came across a Dr Martin Luther King quote saying that there is no amount of money that can adequately compensate the emotional damage done to African Americans by slavery. But he added, there IS a financial calculation that can be done for two and a half centuries of unpaid wages. It’s estimated at something between ten and twelve trillion dollars. That sounds a lot, but it’s probably only about three or four times more than what the US government spent on bailing out big banks and businesses after the 2008 crash.

I’m writing this from New Haven, Connecticut, where I’ve been spending time in the Yale University library. It’s a place that typifies some of the distorted past and present of the nation. Yale was founded and financed in the early 18th century by slave owners. During the Civil War, some of its students fought, in defence of slavery, for the Confederacy, Walking around the campus today, most of it built in the early 20th century, the feeling of enormous wealth and privilege is palpable. It currently has an endowment of $41.4 billion (i.e. money in the bank). That’s more than the GDP of some of the African countries from which slaves were kidnapped. Yale boasts about its economic contribution to New Haven and it is the city’s biggest employer. It’s also its biggest landowner, but like other Ivy League universities, it doesn’t pay property tax on its huge estate, valued at $4.2 billion. This deprives New Haven of a potential source of significant income, when it has a poverty rate of 25%. For the city’s black population, the poverty rate is nearly 30%, double that for white residents.

This is just one example of a failure to recognise and make reasonable amends for wealth that was built from forced, unpaid labour, or its inter-generational legacy. It could be replicated for numerous other elite institutions in the US. This insouciant injustice is part of what drives the demand for reparations.

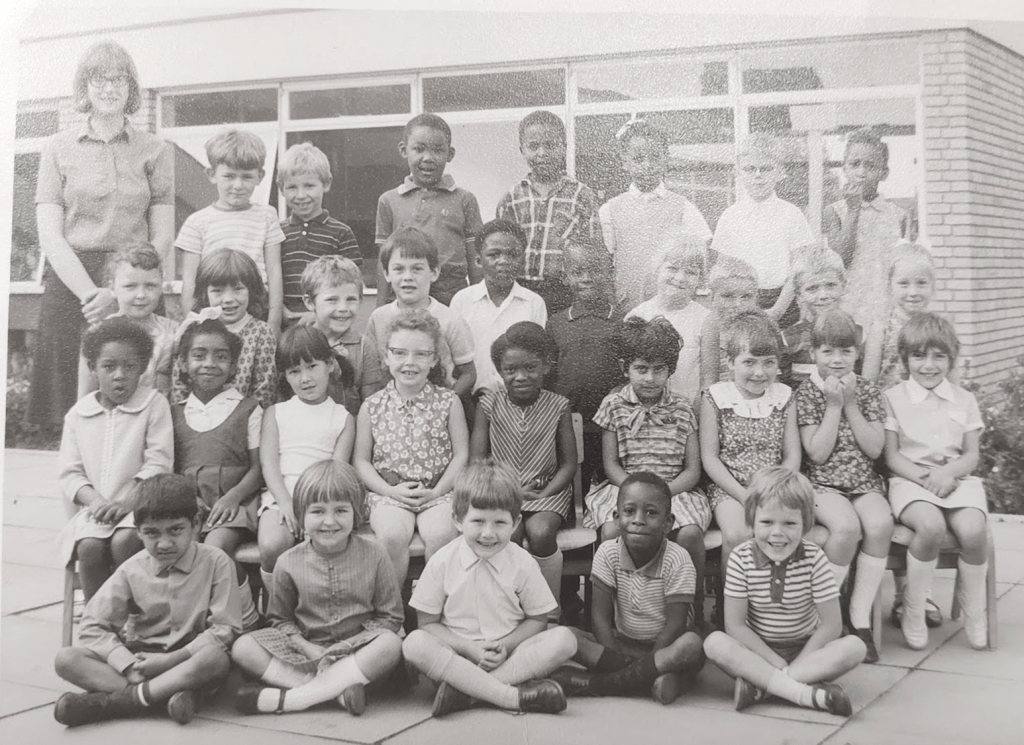

In many ways, the UK is equally culpable. Even before the statue of Edward Colston took an early bath in Bristol Harbour, I’d been aware that Britian’s stored-up wealth of Empire rested heavily on slavery. But, until my time at Rutgers, I hadn’t fully appreciated how deeply buried is that guilty past. A couple of weeks ago, we had a class about reparations, when the students were asked what they learned about slavery during their school years. Unlike most of them, I learnt nothing. Allowing for the difference of 40 years and 3,000 miles, I suddenly realised that, in fourteen years of State education, from 1969 to 1983, I did not receive one single lesson about the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. That was bad for me. But I’ve been thinking about how much worse it must have been for some of my classmates, like those in this picture.

It’s good to see the demand for reparations growing, particularly among the Caribbean Islands, with pressure being applied to some of those who’ve been enriched by slavery, like ex-Tory MP, Richard Drax. But it was equally nauseating to recently hear Keir Starmer say “we don’t pay reparations” because it would lead to “endless discussions about the past”. He, of course, ignores the fact that, until 2015, we were paying “compensation” (valued at £20 million in 1835) to the families of slave owners. Similar payments were made to slave owners in the US.

One of the most frequent objections to reparations is who gets paid and how. To some extent, that’s understandable. It’s almost impossible to know how many African Americans are the descendants of slaves, or for that matter, how many “white” Americans are. But you have to start somewhere. For example, as I walk around US cities, most of the people I see sleeping on the streets are black. They are probably the descendants of slaves. So how about a massive expansion of public and social housing, in the name of reparation? Black people are 15% less likely to hold a college degree in the US, than whites. So how about replicating the post-war Veterans Act and offering free college education to African Americans, in the name of reparations? Something similar could be done around health care.

But these things aren’t going to happen for as long as the country fails to properly acknowledge its history (and in writing this, I’m conscious that I haven’t referred to the genocide of Native Americans). Even then, it will take much more combined pressure to fully right the wrongs. However, in the words of James Baldwin: “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced”.

Leave a comment